|

CURRENT ISSUE

SUBSCRIBE

CONTACT US

ADVERTISING

SEARCH

BACK ISSUES

CONTRIBUTORS'

GUIDELINES

THIS WEEK IN

CALIFORNIA WILD

|

Feature

Still Wild

Ten of California's Untrammeled Places

the Editors of California Wild

If John Muir rose from his Martinez grave and headed

southeast on foot, as he used to do, across the Great Central Valley

(which was, in his day, a blanket of wildflowers growing so close together

an ant could walk from one side to the other without touching ground)

and into the Sierra foothills (then forested with immense oak woodlands,

striped with free-flowing, steelhead- and salmon-running streams, populated

with mountain lions and grizzly bears, and decorated with vernal pools)

and into the beloved peaks of his Sierran "Range of Light,"

and down into his "true home," Yosemite Valley, he might well

continue marching straight to the top of El Capitan and jump to a second

death.

But suppose we caught him before he leapt. How would

we convince him to stay? How would we shake loose his horror of what's

been lost and start him working for the preservation of all that remains?

A glass of Napa Valley cabernet sauvignon? A virtual reality fly-over

of pristine Yosemite Valley with traffic digitally removed? "Fools

gold!" he'd say. Perhaps we could show him a copy of the Wilderness

Act. Or the California Desert Protection Act, or the Endangered Species

Act. "Too late," he'd say. The only hope would be to show

him the new frontiers of California's far outside.

|

The ten places we have assembled here have two things

in common. First, all of them are untrammeled and would still be recognized

as wild by Muir were he to see them today. Second, all remain vulnerable

to the forces that have degraded so much of California's wild lands.

Otherwise, like California itself, they are distinguished, primarily,

by their variety. Not only do they represent a range of California's

habitat types--from rocky Pacific shores to Big Basin desert, from redwood

forest to coastal sage scrub--but also the army of forces that threaten

them. Some, such as the Soda and Avawatz mountains and the San Joaquin

Roadless Area, are already public land. And what threatens them is the

policy of public agencies. Others, such as Headwaters Forest and Bear

Valley, are privately owned, and ultimately may be saved only by an

individual's or organization's commitment. Some, such as the San Simeon

coast and the American River, are threatened by a growing population

and its resource demands. Others, such as the Lost Coast, are vulnerable

to abusive recreation by off-road vehicle enthusiasts. The biological

and natural values of some, such as the Headwaters Forest, have been

well recognized. Others, such as the Buffalo Creek and Smoke Creek desert

complex, remain virtually unexplored.

Diversity is the theme, but all ten deserve whatever

Muirian feats of appreciation and conservation we can muster.

1. Lost Coast (King Range)

The rugged King Range, which abruptly juts thousands

of feet up from the sea, has protected this stretch of coastline from

hosting the roads that spell doom for wilderness. Designated a Wilderness

Study Area in 1979, the King Range, or Lost Coast as it is often called,

is the wildest stretch of coastline remaining in California. Extending

28 miles from the mouth of the Mattole River to Shelter Cove in southern

Humboldt County, it contains old-growth stands of Douglas-fir, coastal

chaparral, the Mattole dune system, as well as riparian habitat in the

undisturbed western watershed of the 4,000-foot-high King Range. Roosevelt

elk, black-tailed deer, seals, sea lions, bald eagles, black bears,

spotted owls, steelhead trout, salmon, and more than 250 bird species

visit the Lost Coast, but few humans do. Once occupied by the Sinkyone

and Mattole Indians, the area contains more than 80 archeological sites.

The Lost Coast's habitat value is amplified by its proximity to Sinkyone

Wilderness State Park and the Sinkyone Inter-tribal Park to the south.

Until Congress decides to officially designate it wilderness, however,

the Lost Coast will remain vulnerable to mining claims, logging, and

off-road vehicle use. For visitor information call the Bureau of Land

Management at (707) 825-2300.

2. Buffalo Creek/Smoke Creek

Desert Complex

At the junction of the Cascade and Sierra Nevada ranges

and the Great Basin lies one of California's least explored but wildest

regions. The buffalo that made up the only California population no

longer roam here, but wild mustangs, kit foxes, coyotes, mule deer,

badgers, and pronghorns still do. Golden eagles are the dominant predator,

and sometimes congregate in large numbers to feast on the abundant jackrabbits

and cottontails. Five California and one Nevada Wilderness Study Areas

are included in this region at the state's eastern border, north of

Pyramid Lake. They make up a series of unconnected high-elevation islands.

The Davis-based California Wilderness Coalition, among

others, recommends unifying these WSAs to create 350,000 acres of wild

lands, including much of the lowland Great Basin desert sagebrush that

connects them. Habitat includes rolling hills, impressive peaks rising

nearly 8,000 feet, long stretches of undisturbed riparian habitat in

the upland areas, stunning sheer-walled canyons, as well as a unique

fusion of juniper woodlands and Sierra Nevada flora. Ongoing sheep and

cattle grazing degrades the plant communities, and off-road vehicles,

driven mostly by hunters, punch illegal roads into the wilderness, making

way for exotic plant and animal invasions, as well as more drivers and

hunters.

3. Headwaters Forest

Sequoia sempervirens, the giant coast redwoods, at

up to 368 feet, are the tallest trees in the world. They require distinctive

conditions: high humidity, supplied by a combination of generous precipitation

and coastal fog, moderate temperatures, and a moist yet sandy soil.

Only in California, along the lower terraces of the Coast Ranges, are

these requirements met. The redwoods have come to exemplify the state's

biological abundance, and with a lifespan of around 2,000 years, they

embody the term "old-growth." Less than four percent remains

of the two million acres of redwood forest that, only 150 years ago,

stretched through California and Oregon. Today, all the surviving ancient

redwood groves are protected. All, that is, except those in the Headwaters

Forest.

The redwoods are the zenith of a rich and diverse

ecosystem that has evolved in their shadow. Alongside the giants, dwarfed

in stature and reputation, are Douglas-fir, grand fir, red alder, tanoak,

western hemlock, and the rare vine maple. Beneath them, in the understory,

are ten-foot sword ferns and evergreen shrubs, and beneath them the

Pacific giant salamanders--and 15 other salamander species--crawl among

the fallen trees. And in the clean, cold streams, wild coho salmon still

spawn. But the most famous denizens flit among the branches--the northern

spotted owl and the elusive marbled murrelet, a seabird which nests

in the old-growth canopy.

Within the Headwaters Forest, adjacent to the 4,500

acres of redwood groves and adjoining residual old- growth forests,

are second-growth forests, recent clear-cuts, and every stage in between.

Some of the second- growth forests are already a hundred years old and

have developed healthy understories, but the multi-storied canopies,

which define an old-growth redwood forest, take centuries to mature.

|

| Photograph by Jo-Ann Ordann |

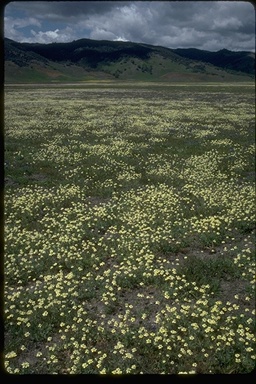

4. Bear Valley

One of the world's greatest wildflower displays is

found in Colusa County's Bear Valley, to the west of Williams and east

of Clear Lake. Though there used to be horizon-defying spring wildflower

displays throughout the Central Valley, there is very little of such

"painted landscape" left in California, and Bear Valley contains

one of the largest remaining patches. In addition to such wildflowers

as the rare pink adobe-lily, and star-tulip, tidy tips, lupines, poppies,

and owl clover, the valley also supports bald eagles, prairie falcons,

golden eagles, Coopers hawks, striped racer snakes, and western pond

turtles. The upland slopes of Bear Valley hold an excellent example

of the increasingly rare California oak woodlands that used to be so

common throughout the area. Walker Ridge, to the west of the valley,

contains serpentine outcroppings that drain into the valley, probably

reducing the competitiveness of many of the exotic weeds that have conquered

so many nearby valleys. Bear Valley has been grazed for a century, but

relatively lightly. Plowing, which disturbs the native habitat elsewhere,

has also been limited here. Walker Ridge, though not as colorful as

the valley itself, is another botanical gem, home to a number of endemics.

A recent attempt to turn Bear Valley into a 20,000-person retirement

complex was stymied by concerned citizens, and the American Land Conservancy

is currently trying to purchase Bear Valley from its current owners

so it can be transferred to a public agency that will protect it in

perpetuity.

5. North & Middle Forks, American River

Encompassing nearly 1,000 square miles of watershed,

the North and Middle Forks of the American River flow through canyons

that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service consider the most pristine of

their kind in the Sierra. Whitewater enthusiasts know the free-flowing

North Fork for its challenging Class IV rapids, but fewer people appreciate

how much wildlife benefits from these two natural corridors connecting

high-altitude conifer stands with foothill woodlands. Ninety species

of neotropical migrant birds, displaced from once-wild rivers in the

Central Valley, use the North and Middle Fork canyons during their international

journeys. Spotted owls depend on the canyons each fall as they migrate

to lower elevations.

The canyons harbor a remarkable array of insects--including

86 kinds of butterflies and the threatened valley elderberry longhorn

beetle. Plants on serpentine soils support critical populations of our

state insect, the California dogface butterfly, plus rare Sierran denizens

like the great copper butterfly and Lindsey's skipper and Wright's skipper

butterflies.

Though the persistent threat of Auburn Dam, which

would inundate 25 miles along each of these river forks, was suppressed

again last year, those who desire additional water supplies and flood

control in the Sacramento Valley will likely bring the plan back to

the table. See for yourself, on foot or from a raft or kayak, what would

disappear if the dam were built.

6. Delta Meadows

The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta was once an immense

triangle of marshland, an intricate web of braided waterways, with the

San Francisco and San Joaquin rivers at its corners and San Francisco

Bay at its apex. In the winter and spring, when runoff from rain or

snowmelt combined with high tides to flood the islands, a vast, shallow

inland sea formed. Levee building, river control, and the agriculture

they allowed began transforming the delta in the mid-1800s, and today

almost nothing remains of the 100 square miles of riparian and marsh

habitat.

The wild past has a refuge, however, in Delta Meadows,

a 500-acre patch of riparian freshwater marsh between the towns of Locke

and Walnut Grove. This maze of unaltered waterways attracts river otters,

beavers, muskrats, black-tailed deer, herons, waterfowl, raptors, cottonwoods,

oaks, and willows. Such a fecund ecosystem drew the Plains Miwok Indians,

too, and Delta Meadows contains a number of important archeological

sites.

Two hundred and fifty acres of Delta Meadows is already

owned by the California Department of Parks and Recreation (CDPR), but

the other, more pristine, half belongs to Asian Cities, a Hong-Kong-based

real estate company. Permitting difficulties have saved Delta Meadows

from at least two development proposals: one for a large marina, and

one for an amusement park. CDPR is currently negotiating with Asian

Cities over an appropriate purchase price for the land, which is, according

to state bureaucrats, a high priority for acquisition.

7. San Joaquin Roadless Area

East of the Sierra Nevada crest, between June Mountain

and Mammoth Mountain and in the shadow of San Joaquin Mountain and the

Minarets, stretches the San Joaquin Roadless Area. These 21,000 acres

of wilderness are home to the headwaters of the once considerable Owens

and San Joaquin rivers. They are also home to black-tailed deer, mountain

lions, black bears, American pine martens, the rare Yosemite toad, goshawks,

and an infrequent southern spotted owl. Fishers scurried through the

undergrowth not many years ago, and if wolverines still inhabit California,

this isolated region is where they are likely to live. The Sierra crest

here is relatively low (11,000 feet) and acts as a corridor for creatures

moving east from the Ansel Adams Wilderness.

In the lush sub-alpine meadows at higher elevations,

spring occasions a wonderful display of minute wildflowers pollinated

by a rainbow of butterflies. On the slopes beside the meadows are forests

of old-growth red fir, rare east of the Sierra divide, and ancient Jeffrey

pine.

Today only the most adventurous hiker and cross-country

skier venture into this remote region, but if the Forest Service's current

plan goes through, there will be a network of ski runs and mountain

bike trails, and all the concomitant infrastructure.

8. San Simeon Coast

From the bluff by the Piedras Blancas lighthouse,

one can spot in quick succession a mother gray whale and calf cruising

by, a sea otter bobbing in the kelp, and the peregrine falcon that nests

on the rock just offshore. To the south, the state's fastest-growing

population of northern elephant seals hauls ashore each winter and spring

to fight, mate, birth, nurse, and molt. Numbering about 4,000 at their

peak aggregation, the seals look like driftwood logs stacked along the

beach.

Newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst chose this

sleepy stretch of San Luis Obispo County coast to erect his palatial

estate, San Simeon, atop the rolling hills. Now the Hearst Corporation,

which owns 83,000 acres of nearby beaches and surrounding ranchland,

wants to build a massive resort on the dramatic Pacific promontory of

San Simeon Point. What's now a fairy-tale forest of gnarled Monterey

pines, used as winter roosts by monarch butterflies, would become Pebble

Beach South: a 650-room hotel, exclusive golf course, convention center,

and dude ranch.

Few doubt that should San Simeon Point become a major

tourist destination, coastal development will spread north and south,

spoiling the scenic and agricultural character of the region and potentially

impacting such declining species as the tidewater goby, steelhead trout,

and California red-legged frog. And though they aren't in decline, the

elephant seals have been annexing additional beachfront north of Cambria

and could colonize the beach adjacent to the Point.

County supervisors narrowly approved the resort in

June. Only the California Coastal Commission stands in the way, and

they meet in January to decide whether or not the Hearst plan violates

the letter and spirit of the state's Coastal Protection Act.

9. Soda and Avawatz Mountains

East of the Army's Fort Irwin National Training Center,

south of Death Valley, the Soda and Avawatz mountains rise out of the

Mojave Desert floor. There are five Wilderness Study Areas here, where

the terrain varies from colorful, geologically stratified slopes to

eroded, jagged ridges, and narrow, steep-walled canyons to gentle, creosote-bush-covered

inclines. The area is home to bighorn sheep, endangered desert tortoises,

Gila monsters, kit foxes, ringtails, and chuckwallas. It also contains

a number of important cultural and archeological sites. The Army is

hoping to expand its training facility by about 300,000 acres to make

more room for troop and tank maneuvers. They are opposed by a wide front

of desert interests, including hunters, off-road vehicle enthusiasts,

miners, and environmentalists. These groups, often at odds in land-use

debates, all agree that these pristine and rugged desert lands are too

fragile and important to trash in war games.

10. Otay Mountain and Mesa

San Diego County has greater biological diversity

than any other county in the continental United States. It also has

more endangered species. Many of these occupy coastal sage scrub habitats

such as those at Otay, one of the largest remaining unbroken expanses

of coastal sage scrub in the world. In addition, the Otay Mesa and Mountain

area contains vernal pools, sizable chunks of maritime succulent scrub,

and stands of the rare Tecate cypress. Otay is part of southern California's

innovative Natural Communities Conservation Program, which, by surveying,

prioritizing, and trading private and public lands, attempts to maximize

conservation efforts while minimizing their economic costs. Although

a 44,000-acre portion of Otay has recently been designated the intended

site for a National Wildlife Refuge, most of that property is still

privately owned, and unless enough funds are found for its purchase

and preservation, it could have a far less wild destiny. Complicating

the story at Otay is the 14-mile-long fence recently constructed along

the border with Mexico, south of the refuge in Bureau of Land Management-controlled

wilderness. The U.S. Government's attempt to control illegal immigration

here has funneled immigrants, and their pursuers, around the fence and

through this extremely sensitive habitat.

|

Winter 1998

Vol. 51:1

|