|

Biological

Synopsis

By

Galen B. Rathbun

Department of Ornithology

& Mammalogy, California Academy of Sciences

|

|

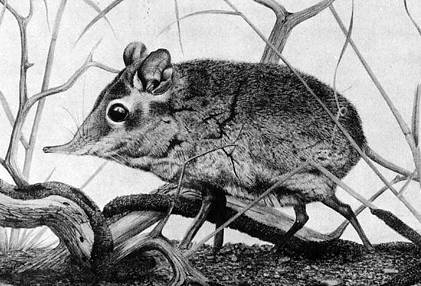

| Face-washing

rufous sengi Elephantulus rufescens |

| Phylogeny | Ecology |

| Taxonomy | Behavior |

| Distribution | Husbandry |

| Morphology | Conservation |

| Physiology | Literature Cited |

Many biologists currently include the sengis in the new supercohort Afrotheria, which encompasses several other distinctive African orders. Few mammals have had a more colorful history of misunderstood ancestry than the elephant-shrews, or sengis. Most species were first described by Western scientists in the mid to late 19th century, when they were considered closely related to true shrews, hedgehogs, and moles in the order Insectivora. Since then, there has been an increasing realization that they are not closely related to any other group of living mammals, resulting in biologists mistakenly associating them with ungulates, primates, and rabbits. The recent use of molecular techniques to study evolutionary relationships, in addition to the more traditional morphological methods, has confirmed that elephant-shrews represent an ancient monophyletic African radiation. Many biologists currently include the elephant-shrews in a new superorder, the Afrotheria, which encompasses several other distinctive African orders. These include elephants, sea cows, and hyraxes (the Paenungulata); and the aardvark, elephant-shrews, golden-moles, and tenrecs (Murphy et al. 2001).

The 17 living species of sengis are well-defined, and their taxonomy is considered nearly definitive (Corbet and Hanks 1968; Nicoll and Rathbun 1990; Rovero, Rathbun, et al., 2008; Smit et al. 2008). All living species are in a single family with two subfamilies. The giant elephant-shrews include the genus Rhynchocyon with four species, and the soft-furred elephant-shrews include three genera. Macroscelides and Petrodromus are each monospecific, while Elephantulus contains 10 species (see Distribution). Elephant-shrews were much more diverse during the Miocene period (about 23 million years ago), when an additional four families existed. Some extinct forms had herbivorous-style teeth that were so similar to the dentition found in living hyraxes that they were first described as hyraxes (Patterson 1965, Butler 1995). The common name "sengi" is being used in place of elephant-shrew by many biologists to try and disassociate the Macroscelidea from the true shrews (family Soricidae) in the order Insectivora.

|

|

| Scratching

rufous sengi Elephantulus rufescens |

Sengis are restricted to Africa, and are distributed throughout the continent with the exception of western Africa and the vast Sahara region (Corbet and Hanks 1968). Southern and eastern Africa are centers of diversity. Macroscelides is only found in southern Africa, and the greatest number of Elephantulus species occur in southern Africa, followed by eastern Africa. Rhynchocyon only occurs in central and eastern Africa. Petrodromus is among the most widespread. One species of Elephantulus is found only along the northwestern edge of the continent, separated from all other sengis by the Sahara.

Rhynchocyon includes the largest and most colorful sengis (see Photographic Gallery). Adults weigh 400-700 g, with head/body and tail lengths up to 310 mm and 250 mm, respectively. The soft-furred species have similar body proportions, but range from about 35 g for Macroscelides to about 200 g for Petrodromus. Species of Elephantulus are 50-60 g. The smaller species are shades of brown and gray (Corbet and Hanks 1968). All sengis are born precocial in small litters (Rathbun 1979, Neal 1995). The long limb bones are adapted for cursorial locomotion (Evans 1942). The relatively long digestive tract includes a caecum (Spinks and Perrin, 1995). Several features of the reproductive tract are distinctive, including the estrus cycle, polyovulation (Horst 1946, Tripp 1971), abdominal testes, and the structure of the penis (Woodall 1995).

|

|

| Four-toed

sengi Petrodromus tetradactylus |

Sengi metabolic rates are typical of most mammals of similar size. However, several species are able to alter their physiology to meet environmental extremes (Perrin 1995a). For example, some species exhibit torpor when they encounter low temperatures (Lovegrove et al. 2001). Their digestive physiology is similar to that of other insectivorous small mammals (Woodall and Currie 1989), despite their likely herbivorous ancestry.

Rhynchoycon and Petrodromus are largely confined to lowland and montane forests and dense woodlands, while Elephantulus and Macroscelides are found in more arid lowlands, such as savannahs, scrublands, rocky outcrops, and deserts. In nearly all cases, sengis are found in low densities compared to many other small mammals (FitzGibbon 1995, Perrin 1995b). At low latitudes reproduction is continuous, but at higher latitudes it is seasonal (Neal 1995). All sengis prey on invertebrates, although most soft-furred species supplement this diet with small fruits, seeds, and green plant matter (Rathbun 1979, Kerley 1995). Snakes, raptors, and carnivores are known predators of sengis. A wide variety of parasites are hosted by macroscelids (Fourie et al. 1995).

Field studies of representatives of all four genera have been completed (Sauer 1973, Rathbun 1979, FitzGibbon 1995). Monogamous pairs defend congruent territories sex-specifically (males vs. males and females vs. females). The giant sengis are strictly diurnal, while the soft-furred species are often crepuscular, with some activity during both day and night. Sengis have well-developed senses of sight, hearing, and smell. Most scent mark their territories with perianal, sternal, subcaudal, or foot glands. Although vocalizations are not common, many species frequently foot drum or tail slap the substrate in stressful situations. Rhynchocyon builds leaf nests on the forest floor, while most soft-furred species use burrows of other species, or construct their own. Some species maintain complicated trail systems through leaf-litter, and several have specialized sheltering habits, such as rock crevices in boulder fields, or relatively exposed spots on runs at the base of bushes.

In the past 20 years, with increasing knowledge of their natural history, several soft-furred sengis have been successfully kept and bred in captivity. These successes have resulted in increased research on captive animals (Perrin 1995b). Although Rhynchocyon is difficult to maintain, it has recently been bred in captivity. Only Petrodromus has not reproduced in captivity (Tripp 1971, Nicoll and Rathbun 1990), even though it is relatively easy to maintain.

On the 2008 IUCN Red List of mammals, most of the 16 sengis (the new Elephantulus is not yet included) are considered "Least Concern", but three species of Elephantulus are listed as "Data Deficient". All four species of giant sengis, however, are at risk. The golden-rumped sengi (Rhynchocyon chrysopygus) is "endangered", the black-and rufous sengi (R. petersi) and gray-faced sengi (R. udzungwensis) are both "vulnerable", and the checkered sengi (R. cirnei) is "near threatened". In all cases the main threat is their restricted or fragmented forest habitats (Nicoll and Rathbun 1990) that are being heavily impacted by logging practices and clearing for agricultural and urban development (Rathbun and Kyalo 2000). Subsistence hunting for food may also be a problem in some areas.

I chose the following citations because they represent seminal contributions to the sengi literature, or they include recent reviews of topics. For additional citations search the Bibliography.

Butler, P. M. 1995. Fossil Macroscelidea. Mammal Review 25:3-14.

Corbet, G. B., and J. Hanks. 1968. A revision of the elephant-shrews, Family Macroscelididae. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Zoology 16:47-111.

Evans, F.G. 1942. The osteology and relationships of the elephant-shrews (Macrosclididae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 80:85-125.

FitzGibbon, C. D. 1995. Comparative ecology of two elephant-shrew species in a Kenyan coastal forest. Mammal Review 25:19-30.

Fourie, L. J., J. S. Du Toit, D. J. Kok, and I. G. Horak. 1995. Arthropod parasites of elephant-shrews, with particular reference to ticks. Mammal Review 25:31-37.

Horst, C. J. van der. 1946. Some remarks on the biology of reproduction in the female of Elephantulus, the holy animal of set. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 31:181-199.

Kerley, G.I.H. 1995. The round-eared elephant-shrew (Macroscelides proboscideus) as an omnivore. Mammal Review 25:39-44.

Lovegrove, B.G., J. Raman, and M.R. Perrin. 2001. Daily torpor in elephant shrews (Macroscelidae: Elephantulus spp.) in response to food deprivation. Journal of Comparitive Physiology Series B 171:11-21.

Murphy, W.J., E. Eisirik, S.J. O'Brian, O. Madsen, M. Scally, C.J. Douady, E. Teeling, O.A. Ryder, M.J. Stanhope, W.W. de Jong, and M.S. Springer. 2001. Resolution of the early placental mammal radiation using Bayesian phylogenetics. Science 294238-2351.Neal, B.R. 1995. The ecology and reproduction of the short-nosed elephant-shrew, Elephantulus brachyrhynchus, in Zimbabwe with a review of the reproductive ecology of the genus Elephantulus. Mammal Review 25:51-60.

Nicoll, M. E., and G. B. Rathbun. 1990. African Insectivora and Elephant-shrews, an Action Plan for their Conservation [20 MB PDF]. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), Gland, Switzerland.

Perrin, M.R. 1995a. Comparative aspects of the metabolism and thermal biology of elephant-shrews (Macroscelidea). Mammal Review 25:61-78.

Perrin, M. R. (editor). 1995b. The Biology of Elephant-shrews - A Symposium Held During the 6th International Theriological Congress, Sydney, 5 July 1993. Mammal Review, Vol. 25, No. 1 and 2. 100 pp.

Patterson, B. 1965. The fossil elephant-shrews (Family Macroscelididae). Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard 133:295-335.

Rathbun, G. B. 1979. The social structure and ecology of elephant-shrews [21 MB PDF file]. Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie Suppl. 20:1-77.

Rathbun, G.B. and S. Kyalo. 2000. Golden-rumped elepant-shrew. Pp 125-129, 340-341 in R.P. Reading and B.J. Miller (eds.). Endangered animals -- conflicting issues. Greeenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut. 388 pp.

Rovero, F., G. B. Rathbun, A. Perkin, T. Jones, D. O. Ribble, C. Leonard, R. R. Mwakisoma, and N. Doggart. 2008. A new species of giant sengi or elephant-shrew (genus Rhynchocyon) highlights the exceptional biodiversity of the Udzungwa Mountains of Tanzania. Journal of Zoology 274:126-133

Sauer, E. G. F. 1973. Zum sozialverhalten der kurzohrigen elefantenspitzmaus, Macroscelides proboscideus. Zeitschrift fur Saugetierkunde 38:65-97.

Smit, H. A., T. J. Robinson, J. Watson, and B. Jansen van Vuuren. 2008. A new species of elephant-shrew (Afrotheria: Macroscelidea: Elephantulus) from South Africa. Journal of Mammalogy 89:1257-1269.

Spinks, A. C., and M. R. Perrin. 1995. The digestive tract of Macroscelides proboscideus and the effects of diet quality on gut dimensions. South African Journal of Zoology 30:33-36.

Tripp, H.R.H. 1971. Reproduction in elephant-shrews (Macroscelididae) with special reference to ovulation and implantation. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 26:149-159.

Woodall, P. F. 1995. The male reproductive system and the phylogeny of elephant-shrews (Macroscelidea). Mammal Review 25:87-93.

Woodall, P. F., and G. J. Currie. 1989. Food consumption, assimilation and rate of food passage in the Cape Rock Elephant Shrew, Elephantulus edwardii (Macroscelidea, Macroscelidinae). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 92A:75-79.

© Copyright 2008 California Academy of Sciences